To some, the word “hedging” has a negative connotation, maybe because it brings to mind high-risk or complicated hedge fund strategies.

But currency hedging is a straightforward management practice for reducing or eliminating foreign exchange (FX) currency risk, like an insurance policy a company can buy to protect its profits from FX movements.

When a U.S. company commits to a future transaction where foreign currency is paid or received, that company runs the risk of losing money if the value of the currency changes before payment is made or received.

Savvy chief financial officers know how to mitigate this risk, tailoring their approach to the specific countries or regions in which their companies sell.

The volatility of the U.S. dollar-euro exchange rate during the first half of 2018 showed the importance of planning ahead. The dollar-euro rate swung from a high of $1.25 per Euro in February to a low of $1.13 per Euro in June, a 10 percent move that had the potential to wipe out profits in some low-margins businesses.

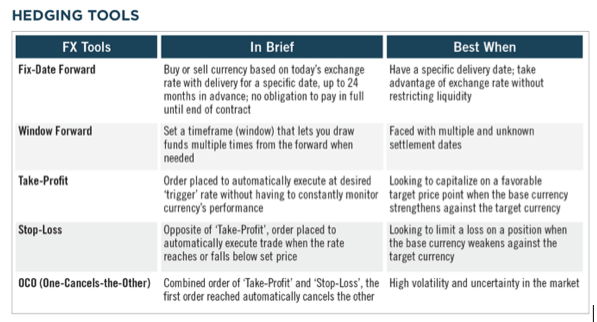

One way companies could have prepared is through a currency hedging tools called a forward contract, where the buyer simply buys currency today for use later. When a U.S. company buys a forward for foreign currency, it is locking in its FX price and eliminating the chance of losing money if the market price of the foreign currency rises by the time the company needs to buy the currency. Forwards typically can be secured up to 12 months in advance, and in some cases out to 24 months. (See “Hedging Tools, below.”)

Most U.S. companies that buy forwards make purchases with foreign currencies. But forwards can also be used by U.S. retailers or exporters selling abroad that know they will generate a given amount of revenue in a foreign currency in the future.

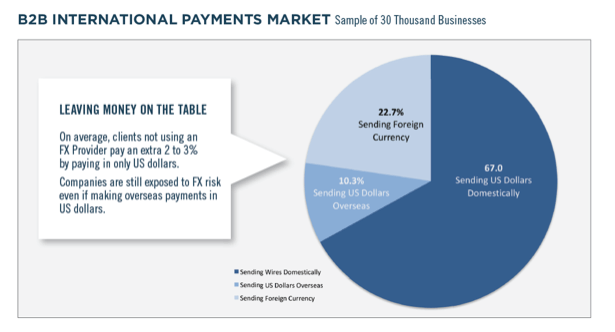

Currency hedging also provides secondary benefits. In the past, U.S. companies commonly avoided the FX risk of making purchases in a foreign country by paying with only U.S. dollars. The downside to this approach is that the foreign seller can pad its U.S. dollar price, as much as 5 percent to 10 percent, to protect itself from currency risk.

When a U.S. company can make its purchases in the local currency, it’s more likely to get a better price. A U.S. company can ask for a dual-currency invoice—in both the foreign currency and the U.S. dollar—and pay in the currency that is most financially beneficial to the company.

CFOs can also employ currency forwards to lock in budgets for overseas operations, buying the foreign currency with ‘Forward Contracts’ when the overseas budget is set. In this way, forwards prevent planned costs from shifting against volatile exchange rates and help CFOs better manage their cash flow since only a small pledge of collateral is due when booking a forward contract. A firm can buy currency forwards to create partial hedges, with contracts that buy half of the expected foreign currency future outlay, to hedge half of the risk, while buying the remainder of the currency on the spot market.

Additionally, finance chiefs can use market orders to buy or sell currency at a set price and within a defined time period to take advantage of shifting exchange rates. A market order simply sets the maximum or minimum price at which you are willing to buy or sell.

Two examples of market orders are the take-profit order, which is an order to buy or sell at a pre-defined price to lock in a profit, and the stop-loss order, which is an order to buy or sell at a pre-defined price to limit a loss. These orders are set and then automatically executed, day or night, so the CFO can set it and forget it—there’s no need to keep an eye on the market.

For example, a CFO could determine the maximum price to pay for foreign currency while preserving the company’s profit. Then he or she would place a stop-loss order that the currency is purchased if the market price weakens to that point. At the same time, the CFO can target a favorable price on the currency and use a take-profit order to purchase the currency if the market price ever improves to that price within the defined time period.

A few real-world examples illustrate the power of these tools, which are based on a careful mix of planning and automation:

1. Toronto Payroll

A U.S. company has an office in Toronto, where it pays its employees in Canadian dollars. At the beginning of the year, the company figures its twice-monthly payroll costs for the next 12 months. Then it buys forward contracts for Canadian dollars to cover 50 percent of its payroll on the 1st and 15th day of every month, locking in half of its FX costs for the Toronto payroll. For the other half, the company buys the Canadian dollars on the spot market when needed.

2. High-end Windows from Europe

A company sells high-end windows for luxury homes in the U.S., buying its product from a European supplier. It pays the supplier for each window project in three installments: one payment upfront, a second when the project is 50 percent complete, and a final payment when the project is completed. Because of the uncertainty of the exact settlement dates, when the company lands a project, it buys three window forward contracts for Euros. Delivery is scheduled based upon the three payment due dates to protect the company’s profit margin.

3. Global Retailer

A large tech company based in the U.S. has extensive European operations and a cash-rich balance sheet. When it sets its budget with monthly outlays for its European business, it buys the euros it will need for those operations on the spot market instead of through forward contracts. Even though the company won’t need the Euros for months, buying on the spot market and holding funds until needed, is another way to mitigate future currency risk— though it does consume cash at the time of the spot trade instead of delaying full payment, which a forward contract allows.

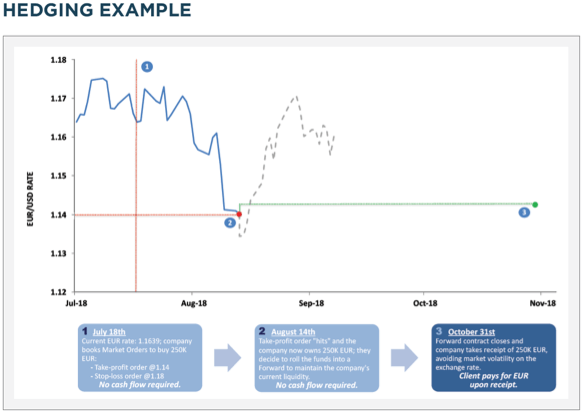

4. Machine Builder

A machine manufacturer based in the U.S. buys components monthly from several suppliers in Europe, paying them in Euros. For a given month of payments to the suppliers, the company knows the total amount due to three months in advance. The manufacturer uses market orders—a “take-profit” order and a “stop-loss” order during the three-month period—to buy the Euros it will need for the payments. It sets the take-profit order at a specific favorable price, so the Euros are purchased if the market price improves to that level. If the Euros market price further declines, the stop-loss order will buy the currency at another specific price before the weakening rate movement eats into company profits. Once either of the orders hits, the firm can pay for Euros, if they have the cash on hand, or roll them into a forward for future delivery. See below:

FX PROVIDER CHECKLIST

The foreign currency market is the largest marketplace in the world. While currencies are a commodity, the level of services and capabilities offered by FX providers varies widely. These are a few of the aspects that CFOs should consider when selecting a foreign exchange provider:

Insight provided by Tempus

Leave A Comment